Our toilet seat at home had to be replaced. A fault line had appeared in the middle. It is pastel peach colour and our plumber tells us that only white toilet seats are being produced these days. We were about to place an order online for a wooden toilet seat that might have been our best alternative. So far I had not taken the initiative to look for a new toilet seat but now that we were about to order a wooden toilet seat, I sprang into action. I googled and found a bathroom accessories shop about ten minutes’ drive away from where I live. I rang up the shop and a lady answered the call quite immediately. I described to the lady about my toilet that needed a new toilet seat. She told me that she might just have what I wanted and she asked me to send her snapshots of my toilet via Whatsapp. Bingo! She had the toilet seat that I needed and that was the last of their old stock. When I picked it up, it was the same make and colour of toilet seat and cover that would well replace the old toilet seat and cover. I was told that the brand no longer made them in that colour. Now that the toilet seat had my attention, I looked up the make online. Indeed, the particular brand still make them in colours but not the colour we want. Can we live with mix and match coloured toilet? I felt lucky indeed.

Due to the pandemic, I was required to provide my name and contact number for the record. It turned out that my sister and the shop owner were classmates and they recently had met during a Chinese New Year get-together lunch. What a coincidence but I would not have known.

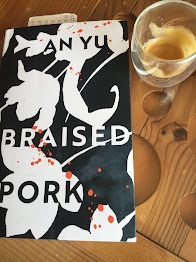

I have just read Braised Pork by An Yu. Another extraordinary young debut novelist. An Yun’s narration is straightforward but her voice is poised hence her delivery is impactful.

One autumn morning in Beijing, Wu Jia Jia finds her husband dead in the bathtub of their central district apartment. Next to him is a piece of folded paper, a sketch of a strange figure from his dream. It is his crude drawing of a creature - a fish’s body and a man’s head.

This is how the story begins:

‘The orange scarf slid from Jia Jia’s shoulder and dropped into the bath. It sank and turned darker in colour, hovering by Chen Hang’s head, like a gold fish. A few minutes earlier, Jia Jia had walked into the bathroom, a scarf draped on each shoulder, to ask for her husband’s preference. Instead she had found him crouching, face down in the half-filled tub, his rump sticking out from the water.

‘Oh ! Lovely, are you trying to wash your hair?’ was what she had asked him.’

It is the month of November and that morning is the first time in weeks he has said something encouraging. He has suggested that they should resume their annual trip to Sanya.

‘ Packing her own belongings were more challenging this time. She had not been able to shop for new clothes – something Chen Hang always told her to do before they travelled.

‘ Go shopping,’ he would say.’ Get some of that new stuff in the windows. You’ll look nice for the beach. And you’ll be happy.’

Maybe she should go shopping tomorrow. But Chen Hang had explicitly told her not to pack too much. Was there a financial issue? Was something going wrong with his business? Again she wanted to interrupt his bath and ask him. Why are you having a bath? You never have baths. Is something wrong at work? She was his wife, not his mistress, she had the right to know. But she felt afraid, as she often was with him, to dig up something that he would rather have kept buried.’

When Jia Jia finds the piece of drawing, she recalls the night her husband had called her when he was in Tibet the first time. He had called her to describe a man who had appeared in his dream and he had been scared by the dream about a fish head that turned into a man’s head. She had not given it much thought at the time but was comforted that he was alone and there had not been another woman on his trip. When she becomes intent on finding out more about this encounter of her husband, she subsequently calls the creature the fish-man.

When Jia Jia finds the piece of drawing, she recalls the night her husband had called her when he was in Tibet the first time. He had called her to describe a man who had appeared in his dream and he had been scared by the dream about a fish head that turned into a man’s head. She had not given it much thought at the time but was comforted that he was alone and there had not been another woman on his trip. When she becomes intent on finding out more about this encounter of her husband, she subsequently calls the creature the fish-man.

Jia Jia knew that her husband had never loved her but they had promised each other a lifelong partnership. Their marriage was purely perfunctory. She is not particularly striking or beautiful, ‘but she is incredibly feminine’. The author writes,

‘ Chen Hang seemed to have recognized that youth and beauty are transient, and so he had chosen her to be his wife; a gracious wife, the kind that a man would take to a dinner party and find, even when his wife was older, that he had become the centre of attention because he had the finest, most tasteful accessory.’

The plot alternates between Beijing and Tibet. In the story, Jia Jia’s relationship with her father is estranged. She arranges to meet with her father at a Shanghainese restaurant and this time she is not going to get upset over his usual nonchalance. She even contemplates about moving to her father’s apartment, thinking that her father is alone and getting old. But her father’s new wife is joining them for dinner. She cannot stop thinking about her mother, ‘the way she’d lain in the hospital bed, pale and hopeless like a white flower petal that had been tweezed off its stem’. When she finds out that her father has remarried, she loses her composure and leaves the restaurant in a huff.

Yu writes,

‘Back when Jia Jia was a small child and morality was a more definite thing, she had chosen to stand with both feet on her mother’s side, offering to her alone- the only victim in her mind – all the love that her young , delicate body could possibly summon.’

Jia Jia has not known much about her parents’ marriage. The title of the book comes from a dish that she shares with her father. It is a moving story. Only in uncovering a past that she has not known, Jia Jia begins to have a sense of her future.

Braised Pork by An Yu is a story about a woman in her early thirties finding herself. Some of the dreamlike narratives in Braised Pork reminds me of the style of surrealism found in Haruki Murakami’s novels. The prose is dreamlike, contemplative and affecting. An Yu is an author born and raised in Beijing.

No comments:

Post a Comment